In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

As commander of the Cork Brigade, Tomás MacCurtain was responsible for the success of his mission. But he had been receiving conflicting orders from the Irish Volunteer HQ in Dublin, writes Gerry White

On the morning of Easter Saturday, 1916, the leadership of the Cork Brigade of Irish Volunteers was in turmoil.

Tomás MacCurtain, the commanding officer, knew that his unit was expected to take part in a major military operation that was planned for the following day, but throughout the week he had been receiving a series of conflicting orders from Volunteer Headquarters in Dublin — a situation that his second-in-command, Terence MacSwiney, described as “order, counter-order, disorder”.

As commanding officer, MacCurtain was responsible for the success or otherwise of his mission. He was also responsible for the safety of his men and as Easter Sunday approached, things were becoming more confused.

MacCurtain’s difficulties began on April 3, 1916, when Pádraig Pearse, the Irish Volunteer director of operations, issued an order for manoeuvres that would commence on Easter Sunday, April 23. It was not unusual for Pearse to issue such an order. However, officers throughout the country were unaware that it was in fact, a cover for an armed rebellion being planned by the secret Military Council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) which consisted of Pearse, Joseph Plunkett, Éamonn Ceannt, Thomas Clarke, Sean MacDermott, Thomas MacDonagh, and James Connolly, the leader of the Irish Citizen Army.

No written copy of the plan conceived by the Military Council survived but some elements are known. The rebellion would take place on Easter Sunday, April 23. The Dublin Brigade of Irish Volunteers and their allies in the Irish Citizen Army and Hibernian Rifles would occupy a number of key locations in the centre of Dublin and establish outposts covering routes into the city. Volunteer units throughout the country would also mobilise.

The task allocated to the Cork Brigade was to occupy a line extending from the Pass of Keimineagh in the north to Newmarket, making contact with the Kerry Brigade in the West. Once in position, they would take possession of their allocation of a supply of German arms that would be brought ashore at Fenit, Co Kerry. MacCurtain had been made aware of his task at the end of 1915 and, that December, MacSwiney conducted a detailed reconnaissance of the ground to be occupied by his unit.

There were many within the senior ranks of the Volunteers who were against a rebellion at that time, including the chief of staff, Eoin MacNeill. To ensure secrecy and thereby increase the rebellion’s chance of success, the Military Council decided not to inform them of their plans. Additionally, in a move that clearly demonstrated their limited knowledge of military procedure, the Council also decided to refrain from informing the Volunteer brigade commanders of their real intentions until the last possible moment.

On April 9, Tomás Mac-Curtain held a conference at his headquarters at the Volunteer Hall on Sheares St, Cork, and issued his order for the Easter manoeuvres. That same day the arms that he expected to receive left Germany on board the SS Aud, a captured British ship disguised as a Norwegian steamer and crewed by members of the German Navy under the command of Captain Karl Spindler.

In summer 1915, Joseph Plunkett and Roger Casement met with the military authorities in Germany. They hoped to secure large quantities of arms, ammunition, and artillery. In the end, however, all they man- aged to obtain were 20,000 captured Russian rifles, ten machine-guns, and 1 million rounds of ammunition.

Roger Casement was unhappy with Germany’s response and he decided to return to Ireland to try and stop the rebellion. Two days after the Aud set sail, he left Germany on board the Ger- man submarine U-19 accompanied by Robert Monteith, the commander of his ‘Irish Brigade’ and Daniel Bailey, a member of that unit. However, with the Aud on the high seas the die had effectively been cast, and the Military Council decided the time had now come to in- form the Volunteers brigade commanders of their mission on Easter Sunday.

On Monday, April 17, Brigid Foley, a member of the Dublin branch of Cumann na mBan arrived in Cork with a sealed dispatch for Tomás MacCurtain from Seán MacDiarmada. The contents of this despatch are not known but when he read it, MacCurtain felt he needed clarification.

He asked Terence MacSwiney’s sister, Eithne, to go to Dublin that Wednesday to see if she could arrange a meeting between the Military Council and her brother. When she arrived in Dublin, she met Thomas Clarke who told her the council were not prepared to meet him at this stage.

While Eithne MacSwiney was in Dublin, the Military Council took a step designed to get Eoin MacNeill to place the Volunteers on a war footing. They released what became known as the Castle Document, a forged document purporting to have been issued by Dublin Castle giving orders for the suppression and disarming of the Volunteers.

MacNeill was taken in by this piece of subterfuge and issued orders for all Volunteers to resist if any move was made against them. However, on the following day, the Military Council’s plans started to unravel.

The Aud arrived off the coast of Fenit on Holy Thursday but, because of a breakdown in communications, the local Volunteers who were supposed to be there to unload the arms failed to appear. Then, that evening, Bulmer Hobson, a senior member of the IRB and Volunteer staff officer found out about the Aud and he immediately informed MacNeill.

MacNeill was furious at having been deceived. Accompanied by Hobson and Commandant JJ ‘Ginger’ O’Connell, the Volunteer chief of inspection, he went to St Enda’s College and confronted Pearse at St Enda’s College.

When Pearse admitted the truth, MacNeill declared that, short of informing the police, he would do every- thing in his power to stop the rebellion. Accordingly, in the early hours of Good Friday, April 21, he issued a general order reaffirming his instructions to take defensive measure only. He also ordered O’Connell to travel to Cork to give this order to MacCurtain.

Later that morning Pearse, and MacDiarmada called to MacNeill’s home. After a heated debate, they convinced him that it was too late to stop the Rising and MacNeill agreed to countermand his previous order. MacDiarmada then contacted Volunteer James Ryan and ordered him to follow O’Connell to Cork with a new dispatch stating that the manoeuvres would take place as originally planned.

JJ O’Connell arrived in Cork on Friday night. He met MacCurtain and MacSwiney at the latter’s home on Victoria Rd and gave them MacNeill’s order in relation to defensive measures. However, un- known to any of them, the situation had already taken a turn for the worse. That morning the Aud had been intercepted by the Royal Navy and Roger Casement had been arrested by the RIC after he came ashore at Banna Stand.

On Saturday morning, MacCurtain was in the Volunteer Hall when James Ryan arrived from Dublin with MacDiarmada’s dispatch. Though frustrated by this latest development, he informed Ryan that he would mobilise his men as planned. But in Dublin the situation was about to change again.

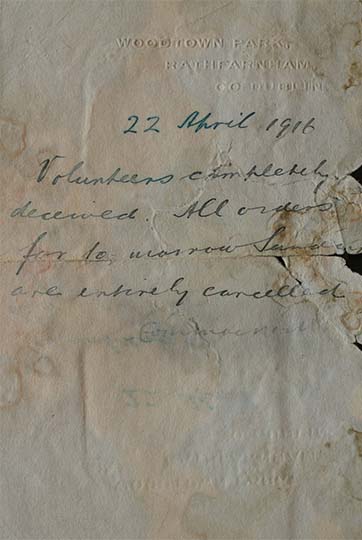

That morning MacNeill learned that the Aud had been intercepted and Casement arrested. Convinced that the rebellion was now doomed to fail, he immediately issued another order cancelling the manoeuvres and placed a notice to this effect in the Sunday newspapers.

He then ordered James Ryan, who had just returned from Cork, to travel back to the city by car early the following morning and deliver his order to MacCurtain.

On Easter Sunday morning, Volunteers all over Cork set out for one of eight designated assembly points. At noon, more than 160 members of the Cork City Battalion, together with others from Cobh and Dungourney, formed up outside the Volunteer Hall. After an address by MacCurtain, most marched off to Capwell Railway Station where they boarded a train for Crookstown, while others were to cycle the route.

MacCurtain had arranged to travel to West Cork by car. However, just as he was about to leave, James Ryan arrived and handed him MacNeill’s la- test order.

Terence MacSwiney had been correct when he de- scribed the events of the past week as “order, counter-order, disorder”.

MacNeill’s action had placed MacCurtain in a difficult position.

With his men on the move all over the county, he was now faced with the prospect of trying to restore some real order to his unit.

The following week would prove just how difficult that task would be.

■ Gerry White is a military historian and co-author, with Brendan O’Shea, of Baptised in Blood: The formation of the Cork Brigade of the Irish Volunteers 1913-1916 (Mercier Press)