News

What we can learn from the extraordinary microbiome of Irish Travellers

This opinion piece by Prof Fergus Shanahan was orginally published by RTÉ Brainstorm 3/5/2023

Opinion: aside from confirming the distinctiveness of Irish Travellers, the microbiome findings also highlight important public health policy lessons

There is an opportunity to challenge conventional thinking when the unexpected happens, but exceptional findings are a lost opportunity if ignored or dismissed as outliers. Similarly, society is impoverished if the contributions and experiences of minority groups are not valued.

When Irish Travellers were unexpectedly found to have an extraordinary microbiome - different not only from that of the rest of the Irish but also from most of the western world - the discovery was more than a scientific confirmation of the distinctiveness of this ancient ethnic group. It also raised important lessons for everyone with implications for public health policy.

The microbiome is the community of personal microbes living in and on the body of all humans. It is a highly variable collection of bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi, mainly shaped by one's environment and life experiences. Evolution ensured that these microbes occupying the human body were selected for promoting health; they protect against infections, assist digestion, facilitate metabolism and nutrition, train the immune system and contribute to brain development.

Most of our understanding of the human microbiome is from studies of affluent people in socio-economically developed countries. Since difference is the essence of humanity and underpins the promise of personalised medicine, the under-representation of ethnic outsiders and minority groups in science is a missed opportunity.

The microbiome of Travellers is similar to that of the pre-industrialised world, whereas the microbiome of the settled (non-Traveller) community diverged with the adoption of modern lifestyle. Retention of an ancient type of microbiome by the Travellers relates to their traditional ways. It is particularly associated with large family size and living in close quarters, in proximity to animals especially horses during childhood. The ancestral microbiome of Travellers is similar to that found among people in non-industrialised societies in Mongolia, Africa, and South America. Such microbiomes have several health advantages including resistance to chronic inflammatory diseases.

But lessons for the rest of society may be lost if Travellers and other minorities are neglected. The most obvious is the prospect of mining ancient microbiomes for their health benefits. In addition, minority microbiomes challenge the concept of a normal microbiome in a multi-ethnic society. They question whether microbiome-based therapeutics including uniform dietary guidelines apply equally to different human populations.

In an era of transcontinental mass migrations, the public health implications of the diverse microbiomes of minorities and outsiders will become more pronounced. Curiously, the discovery of the microbiome began with an outsider. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek was outside the established scientific community and had no scientific credentials other than his curiosity.

Imagine the moment when he peered into his homemade microscope and saw what no man or woman had ever seen or contemplated: tiny creatures living in his stools, mouth and all around him. Lacking fluency in scientific language, he recorded his extraordinary discovery with simple, non-technical words ('little animalcules…a swimming very prettily').

That was over 300 years ago, but then the world forgot. Ignored for centuries, Antonie’s 'little animalcules’ were not even considered by Darwin when contemplating the evolution of the species by natural selection. The opportunity to realise that humans live in a microbial world and that most of the diversity of life on the planet is microscopic, was lost. Many of the species that have become extinct since Antonie’s time have been microscopic, out of sight. Now scientists are concerned that the story of Irish Travellers and their remarkable microbiome may also become one of extinction.

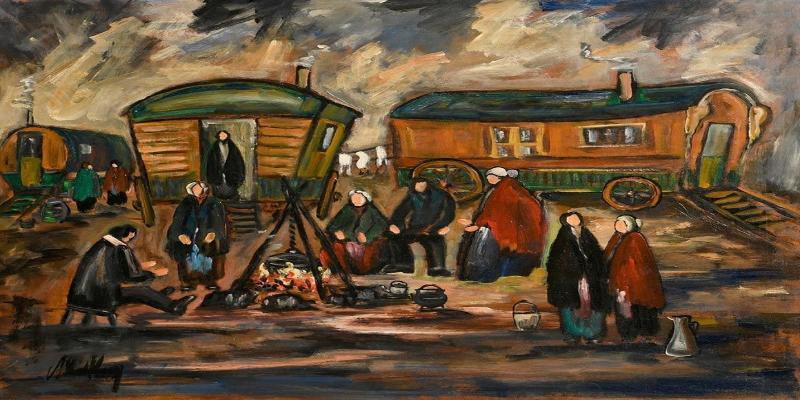

Irish Travellers represent one percent of the population of Ireland. Their lives have been captured in art, narrative and photography and reflect a bygone world. Although their distinct ethnicity has been officially recognised, no effective policy has emerged to protect their ancient culture. While modern Ireland was becoming one of the wealthiest countries in the world, the culture of Irish Travellers was progressively being eroded.

Pressure to abandon Traveller lifestyle has been accelerated by a series of legislation, notably a Housing Act in 2002 which never mentioned Travellers, but which restricted their access to land for temporary living, and effectively ended their nomadism. Since then, Irish Travellers have been restricted to halting sites and state-sponsored housing. Like the microscopic world, they are out of sight. The popular sentiment of inclusivity in modern Irish society does not seem to extend to the Travellers: "we live in the shadows of racism, discrimination and oppression daily".

Individuals who become marginalised because of race, sexual identity, gender, socioeconomic status or otherwise are at increased risk of many diseases. The foreshortened life expectancy and health inequities of Irish Travellers, including alarmingly poor mental ill-health and suicide rates, have been widely reported.

However, racism and discrimination have other negative effects on health which are unseen because they affect the microbiome, and are therefore likely to be ignored. Societal inequities have been shown to adversely alter the microbiome and amplify inequities by negatively affecting health. The dilemma for Irish Travellers is particularly fraught. They are losing more than their traditional way of life; they also seem to be losing the distinctive features and health benefits of their microbiome.

The story of Irish Travellers and their vanishing microbiome is a lesson on misguided policies of assimilation. It is a lesson for public health policy makers on the hidden adverse consequences of pressuring indigenous or migrant ethnic minorities to change. Loss of an ancestral microbiome may be the price to be paid for modernisation, but it doesn’t have to be that way. It could become an exciting story for everyone if we learned how to retain the benefits of a non-industrialised microbiome in a modern society. This won’t happen as long as the fate of a tiny minority in a tiny country is ignored. Opportunity lost.

The author would like to acknowledge and thank the Traveller Visibility Group Cork for their ongoing support and collaboration with APC Microbiome Ireland.