- Home

- About

- Student Led

- Research Informed

- Practice Focused

- Resources

- News

- Green Campus Podcasts

- Case Studies

- Green Labs Community

News

Degrowth: Exploring a Post-Growth Approach

The world has warmed by 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels. Despite progress in climate action globally, we’re not on track to keep warming at or below 1.5C1, as agreed internationally in the Paris agreement of 2015. At 1.2°C, we’re already witnessing devastating weather events and migrations of climate refugees. Predictions of how a warming world would affect life on earth have proven to be, in many instances, conservative. Fossil fuels are still being extracted and burned, the minority world or “global north,” continues to extract natural resources from the global south in an example of intra-species parasitism, and we are in an extinction crisis, with biodiversity being bashed from all angles.

But before you get the wrong idea - this is not a climate-related blog post about the end of the world. It’s about the start of a new one.

In this post, I’m focusing on the role our globalised economy has to play in destroying – but also, conversely, saving – our world.

A tricky subject

Economics is an intimidating subject for many of us, but in essence, it is a “social science concerned chiefly with description and analysis of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.” Economics studies how money flows and where it goes.

Explaining the painful, colonial history of today's economics would take several blog posts. Broadly speaking, we live in a globalised capitalist economy. The health of the economy is measured by how much it grows; indeed, two consecutive quarters without economic growth is a recession. Because our economy needs to constantly grow to function, we need to continually create new goods and services to expand it. But more growth means that more natural resources are used up, there’s more pressure on people to work harder and longer, and more waste is made.

Many of the economic policies which led to today’s growth imperative are rooted in neoliberal thinking of the 20th century. Neoliberal policies often mean that rich people come out on top, while poor people – and the natural world - suffer. This approach to economics also exacerbates existing power imbalances relating to race and geographic location.

Everything comes back to money

Due to its extractive and unequal design, our current economic model has been determined by many to be the root cause of current environmental crises, as outlined by Niamh Guiry in a recent UCC Green Campus blog post. Cheap fossil fuel energy is needed to grow economies. Land and natural resources are needed to accumulate capital, so nature suffers - as do the people on the land. Even though human beings are for the most part good, our economy is not governed by morality; profit is priority.

Growth-dependent economies have not used resources sustainably, and have broken planetary boundaries. Despite what proponents of “sustainable,” economic growth might say, evidence suggests that decoupling GDP growth from environmental damage isn't possible2.

“(…) there is a bitter irony to the fact that we have been persuaded to use the word “growth” to describe what has now become primarily a process of breakdown.” – Jason Hickel

Many economists now believe that the only way to ensure a sustainable future is to replace economic growth with human and environmental welfare as the end goal of our economies. This is where Degrowth comes in.

A potential solution

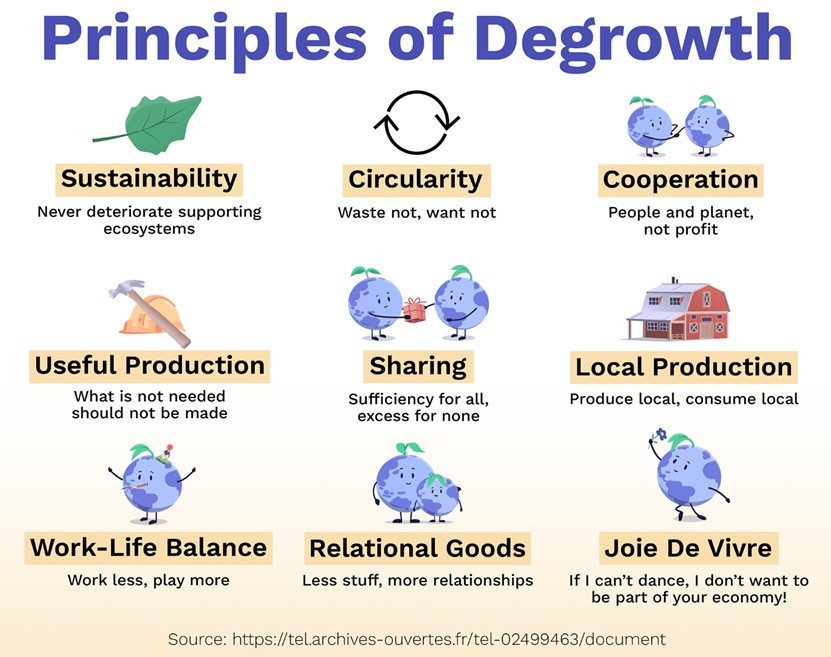

As defined by the World Economic Forum, Degrowth “broadly means shrinking rather than growing economies, so we use less of the world’s energy and resources and put wellbeing ahead of profit”3. Degrowth’s aim is not to reduce GDP, but to reduce consumption and exploitation.

“Degrowth (...) differs from other concepts of sustainability in that it argues in favour of the downscaling of production and consumption, a deviation from a growth, profit, and accumulation orientated narrative, economy and mentality. Degrowth is not, as it may seem, the opposite of quantitative growth, but rather a profound cultural, qualitative change.” - Iana Nesterova

Degrowth accepts that many wealthy economies have reached their growth limit. It advocates for the democratisation of international financial institutions, and for an end to third world debt to reduce the power that rich countries have over poor countries.

Degrowth economies call for and end to destructive industries and unnecessary production4. For example, in a Degrowth economy, private jets, fast fashion, luxury cars, and over-production of animal products would be obsolete.

Under Degrowth, energy and resources would be channelled into meeting human and environmental wellbeing. Some features of a post-growth economy include:

- Universal basic services: to meet people’s needs with minimal resource use

- The end of planned obsolescence (wherein products are built to fail, to encourage repeated buying)

- A green jobs guarantee, where jobs meet social and ecological needs

- Reduced working hours, which could distribute employment opportunities and give workers more time in which to engage in sustainable, healthy lifestyles

- Cancelling of debts and structural adjustment5, 7 imposed upon low-income countries

- Business organised around social and ecological need, rather than growth and short-term financial gains of shareholders

- Reduced advertising, which would result in reduced pressure to consume

- Well-funded and managed green and blue spaces and wild areas to meet social and ecological needs

- Relocalisation of economic activity and currencies, handing control to communities rather than institutions

- Maximum incomes established to promote equality

Looking at Degrowth for the individual, it wouldn't be the same for everyone. For example, if the wealthiest 10 percent of people, who are responsible for half of all global emissions, were to reduce their emissions to that of the average European, we could cut emissions by a third. For the majority, life impacts wouldn't be that major. Broadly speaking, degrowth would result in the establishment of socially cohesive communities who use resources responsibly, who have more time for sustainable living practices (growing and cooking food, repairing products, buying second-hand, sharing resources such as cars and appliances) and who have the autonomy to explore concepts like community currencies and eco-communities.

“degrowth is not about reducing GDP. It’s about reducing the material and energy throughput of the economy to bring it back into balance with the living world, while distributing income and resources more fairly, liberating people from needless work, and investing in the public goods that people need to thrive.” – Jason Hickel

Degrowth proposals would have to be financed by higher taxes, with focus on the wealthy, but the idea is that redistribution would result in fairer, sustainable societies6. Degrowth policies would also need to be democratically developed in accordance with a particular area’s needs; for example, a low-income country may need to grow its GDP, but this could be done in a socio-ecologically sensitive way.

There are of course criticisms of Degrowth, but the world can't go on as it is. In the 1970's, Donella Meadows and her colleagues wrote a report called "Limits to Growth," which highlighted that continuing with business as usual would result in economic collapse in the late 21st century – a prophecy that is currently proving true.

Donella Meadows. Illustration by Irene Ní Shúilleabháin.

Inspiration for the future

In May of this year, the EU held a Post-Growth Conference. Frances Lawson, a conference attendee, led the creation of a Post-Conference Declaration, and invited attendees to add their name to it. The declaration calls for the establishment of an economic model in Europe which replaces GDP with human and ecological well-being as its primary goal, and calls for the coordination of a post-growth future, among other demands. I have never been happier to add my name to a document.

I am excited by Degrowth because it is pragmatic, not idealistic. One of the reasons that Degrowth seems utopian is that appeals to people's goodness and intelligence. Neoliberal capitalism does the opposite of that. Rethinking the growth imperative invites us to think about what we really value - wellbeing, community and the living world.

We are at a critical point where there has never before been such demand for positive change; from climate activists, civil rights actors, scientists, peace advocates, leaders, and most importantly:ordinary people who would love to go for that pint, but have to post a letter and do their taxes and feed the cat and collect the kids.

The quote, “It is now easier to imagine the end of the world then it is to imagine the end of capitalism,” is attributed to Frederic Jameson. May the collective imagination of the loving, compassionate, determined human beings of this world prove him (happily) wrong.

References

- World Meterological Organisation (2023) Global Annual to Decadal Climate Update. Target years: 2023 and 2023-2027.

- Hickel, J. and Kallis, G. (2020) Is green growth possible? New political economy, 25(4), pp.469-486.

- World Economic Forum (2022) Degrowth: what's behind this economic theory and why it matters today | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

- Remblance, E. (2022) Life in a Degrowth Economy and Why You’ll Love It. org; originally published by Medium.com. Life in a Degrowth Economy and Why You’ll Love It - resilience

- Forster, T., Kentikelenis, A.E., Stubbs, T.H. and King, L.P. (2020) Globalization and health equity: The impact of structural adjustment programs on developing countries. Social Science & Medicine, 267, p.112496.

- Cassidy, J. (2020) Can we have prosperity without growth? The New Yorker, Dept. of Finance Can We Have Prosperity Without Growth? | The New Yorker

- Hickel, J., Sullivan, D. and Zoomkawala, H., 2021. Plunder in the post-colonial era: quantifying drain from the global south through unequal exchange, 1960–2018. New Political Economy, 26(6), pp.1030-1047.

This blog post was hugely inspired and informed by Hickel, J. (2020) Less is More: how Degrowth will save the world, published by Penguin Books.