In This Section

The Challenge

The Hidden Galleries project addresses a contested aspect of Europe’s common heritage, the problematic legacy of totalitarianism and its secret police. In the post Cold War-era, the communist and fascist pasts have become a battle ground in the search for historical truth and national memory. In 20th century Central and Eastern Europe, the secret police was one of the principal agencies deployed by both communist and right-wing dictatorships to eliminate undesirable groups from society, significant amongst which were the many undersirable and suspect religious communities.

But in doing this a paradoxical thing happened – testimonies, photographs, personal and sacred items, and the ephemera of religious life were preserved by the very state institutions whose role it was to delete them. Alongside these materials, the secret police produced their own representations of religious groups they were tasked with surveilling and controlling. The materials that were used to incriminate members of religious groups have a dual identity as today they also stand testimony to the creativity and resistance of these communities.

How should we approach this difficult aspect of cultural patrimony? What are the meanings and uses of the secret police archives in the deeply divided societies of contemporary postcommunist eastern europe? In exploring these questions, the Hidden Galleries project has three main aims. Firstly, to improve accessibility to difficult to locate materials throught the creation of a Digital Archive for use by scholars and communities. Secondly, to engage with communities that were targetted by the secret police in conversations about their lost cultural patrimony and its meaning for these communities today. Finally, to open up scholarly and societal debate on the legacies of communist and right-wing repression and how this has shaped post-communist societies.

The Research

Funded by a European Research Council award, eight researchers1 sifted through hundreds of thousands of pages of files in the secret police and other state archives in Romania, Hungary and the Republic of Moldova in order to find the uncatalogued, visual and material traces of communities that had been targeted by the state. A selection of these materials have been digitised and made accessible to researchers and communities in an online open-access Digital Archive.

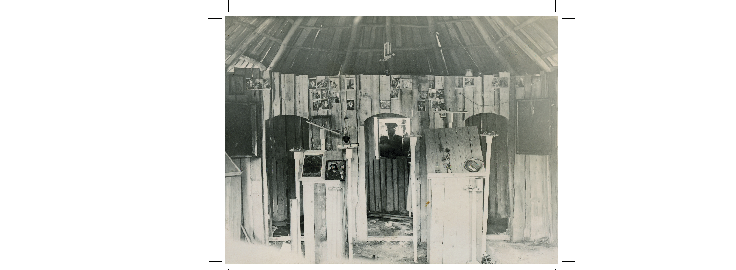

Secret police photograph of confiscated religious materials from Soviet Ukraine featured on the Hidden Galleries Digital Archive http://hiddengalleries.eu/digitalarchive/s/en/item/195

The various archival institutions have different regimes of access that impact on who gets to read a file, when and under what circumstances. Very rarely do members of the smaller religious communities that were targeted know what kind of materials can be found there or how to gain access. Following on from our archival work, whenever possible, the project researchers approached individuals and communities to discuss their experience of repression, their relationship to the archival materials that were stolen from them, to explain how to gain access and to invite them to participate in the project's public exhibitions taking place between November 2019 and June 2020 in Hungary, Romania and Moldova. In addition, the project team are producing a series of scholarly publications that address historical, visual methodological, anthropological and ethical questions in relation to the uses and meaning of the secret police archives.

The Impact

The secret police were mostly interested in people, not in preserving objects and images, but paradoxically that is precisely what they have done. Unintentionally, the secret police created the possibility for the personal artefacts and cultural patrimony of communities to experience a new life and for researchers to pose new questions. The opening of the secret police archives from the 1990s onwards was designed to give access to those who were the targets of the regime as a form of compensation but this has not been taken up by groups, geographically removed from archives located in capital cities or who lack knowledge and know-how related to accessing state institutions.

The Hidden Galleries project has made accessible for the first time a wide range of materials and resources that were previously the preserve of a small number of accredited researchers. Open access to these examples of visual and material religious items is designed to achieve two aims. Firstly, to encourage scholars to incorporate visual and material methodologies in their research on communist and fascist repression of religion. Secondly, to reconnect communities with aspects of their lost cultural patrimony.

“Everyone thinks that the archives are for researchers, not for them. But in fact, it’s very important for people to understand that the archives can be accessed! This project has motivated people to do more research. Your work is extremely valuable for us, it is as if we opened a box and now they can look inside it and discover more” (a member of the Old Calendarist Church, Romania)"

Members of the choir from Ocna Sibiului at the Hidden Galleries exhibition in Cluj-Napoca looking at photographs of their forebears that had been confiscated by the secret police

This second goal has achieved almost immediate results with members of religious communities having contacted the Principal Investigator and members of the research team by telephone and via facebook to discuss the materials we have found and placed online. These connections have developed into close partnerships with the project team helping communities (e.g. the Old Calendarist Church and the Reformed Church Choir from Ocna Sibiului) navigate access to the secret police archives as well as with communities contributing to the project team’s analyses of images and objects. As project curator Gabriela Nicolescu reflects, the process of selecting of objects and stories for the exhibition became a tool of research in itself while having the images blown up large on the wall, produces a different encounter with the visual material both for the researchers and our research participants.

In preparation for the public exhibitions that are taking place from November 2019 to June 2020, we have engaged with communities regarding the materials we found in the archives and together with them we pose some critical questions: To whom should these personal or sacred objects belong? How should they be preserved? And who should control access to them?

“They should be given back to the community, or at least given to museums that can preserve and exhibit them. The community should be the rightful owner of these items because it produced them, the believers made them. Not showing these items is not a right, it’s an abuse” (Tudorist believer)"

An example of surveilance photography form 1970s Romania featured in the Hidden Galleries Digital Archive http://hiddengalleries.eu/digitalarchive/s/en/item/385

As well as giving access to religious communities and scholars, it is also the aim of the project’s public exhibitions to stimulate wider public debate on the legacy of totalitarianism and its impact on how society relates to questions of “otherness”. Working with groups of second level (highschool) and university students in Ireland, Hungary, Romania and Moldova, the project team is exploring, thorugh a series of interactive events, how the secret police used photographs, film and graphics to identify, incriminate and marginalise religious groups and to relate this to their own use of images on social media and to contemporary debates on privacy, access to personal data and the projection of “social danger” onto diverse segments of society.

Students from the Art Highschool “Romulus Ladea” in Cluj-Napoca in the Hidden Galleries exhibtion.

The success of the key outputs of the project are the result of the establishment of a wide range partnerships and collaborations with institutions including the Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives in Romania, the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security in Hungary, the Museum of Art in Cluj-Napoca, Romania, the National Museum of Ethnography and Natural History in Chișinău, Moldova, the Open Society Archives in Budapest as well as several university departments and schools in the region.

The Hidden Galleries project aspires to be open-ended encouraging wider circles of scholars and communities to become involved in enlarging the Digital Archive and taking the public exhibitions to other venues around the region.

For more information contact the project lead Dr James Kapaló at hiddengalleries@ucc.ie or you can follow the project on our website

http://hiddengalleries.eu/ and on facebook and twitter @hiddengalleries. Explore our Digital Archive at http://hiddengalleries.eu/digitalarchive/s/en/page/welcome.

College of Arts, Celtic Studies & Social Sciences

Coláiste na nEalaíon, an Léinn Cheiltigh agus na nEolaíochtaí Sóisialta

Contact us

College Office, Room G31 ,Ground Floor, Block B, O'Rahilly Building, UCC