A biography of Andreas Vesalius

A Biography by Dr André Toulouse

Of the great names in Anatomy and Medicine, Andreas Vesalius stands out as having revolutionized the way medicine was taught. Through his refusal of accepted knowledge, relying on personal experience rather than books, he broke centuries old dogma that had crippled the evolution of medicine.

Andreas Vesalius (Dutch Andries van Wesel) was born in Brussels on the 31st December 1514 to a family of apothecaries. He began his arts studies at the University of Louvain before moving to Paris, then one of the best medical schools in Northern Europe, to study medicine. There, he studied under the tutelage of Jacobus Sylvius and Ioannes Guinterius Andernacus who would have been teaching along the precepts of the roman physician Galen of Pergamon (129-216 AD). Obtaining his degree in medicine in 1533, he later moved to Padua, Italy where he obtained the title of Doctor of Medicine in 1537.

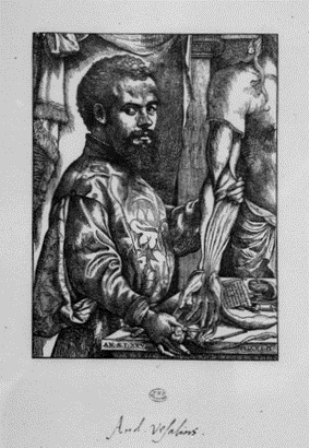

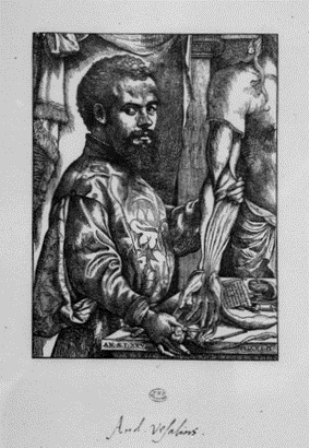

Portrait of Andreas Vesalius. Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire de Santé (Paris)

It is said that throughout his studies, Vesalius grew frustrated with his learning experience. At the time, anatomical teaching heavily relied on texts written by Galen who had focussed on animal rather than human dissection. While some of the text had been modernized by anatomists such as Mondino de Liuzzi (1270-1326), the teaching methods remained anchored in the middle ages. During dissection, the professor sat in a high chair, teaching from a Galenic textbook, while a surgeon was performing the dissection. Any divergence from the text would be dismissed as an anomaly.

The day after his graduation, at the age of 24, Vesalius was offered the chair of surgery at the University of Padua. There, he would free himself from the dogma that he had felt crippled his knowledge of anatomy and favour a new “hands-on” approach. Eighteen months later he published a visual aid for his students, the “Tabulae anatomicae sex” with engravings from Jan van Calcar, which would confirm his growing reputation as one of the leading European anatomists.

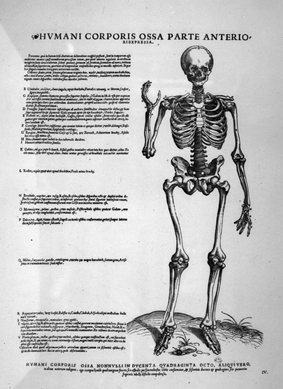

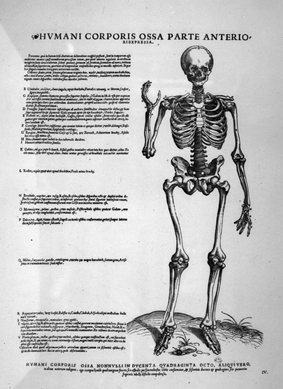

Re-impression of plate 5 of the Tabulae anatomicae sex (1538) by Andreas Vesalius / Jan van Calcar. Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire de Santé (Paris)

Over the next few years, Vesalius undertook the work that would lead to the creation of his masterpiece “De humani corporis fabrica” which was published in 1543 by Johannes Oporinus in Basel. By then, Vesalius’ reputation had grown beyond the confines of academia and he was appointed to the medical team of the Holy Roman emperor Charles V. During his time in the service of the emperor, Vesalius perfected his skills as a surgeon, developing new methods to remove pus from the body cavities, allowing the treatment of wounds that would otherwise be fatal.

After the war with France erupted (1551-1559), he returned to Brussels where he would prepare the second edition of the Fabrica, published in 1555. This second edition not only corrected errors from the first but also contained considerable improvements based on Vesalius’ increased anatomical experience and knowledge. He strongly rejected Galenic views, encouraging his students to question traditional descriptions, including his own, and demanding that they pursue investigation into new findings.

In 1556, after Charles V abdicated, Vesalius was appointed as physician to King Philip II of Spain. Three years later he was called to the French court to treat Henri II who had been injured while jousting. Although the king of France died from his wounds, Vesalius’ reputation was such that he was appointed to perform the autopsy. During his time at the Spanish court, Andreas Vesalius wrote what would become his last essay, a text supporting the anatomical observations of his contemporary Gabriele Falopio. In 1564, perhaps as a way to escape the Spanish court, Vesalius undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Upon his return, the ship was caught in a storm and washed ashore on the Greek island of Zakynthos where he fell ill and died.

Vesalius’ legacy still permeates anatomy and medicine today. The creation of a book that carefully and systematically introduced anatomy of the human body in a way that was truthful to the findings of dissection had never been accomplished to this scale before, laying the foundation for the modern medical textbooks in use today. While his contribution to anatomy and medicine is undeniable, Vesalius’ challenge of Galen’s teaching and encouragement of anatomists and students not to rely on accepted knowledge, also contributed to the establishment of medical science as a structured discipline. He first saw the importance of learning through one’s own experience and understood how this could improve the acquisition of new knowledge. While modern medical education perpetuates many of the principles established by Vesalius, most importantly, we should not forget to question and review our knowledge and methods. Following Vesalius’ footsteps, we must remain open to challenges and acknowledge the diversity of learning experiences.