Under the sea: finding out more about corals in the Atlantic Ocean 02 Oct 2020

By Aaron Lim, postdoctoral researchers at the Environmental Research Institute and iCRAG, UCC

Analysis: offshore research expeditions are discovering a rake of new findings about cold-water corals in the Atlantic

For most, the word "coral" is associated with shallow tropical seas and sunshine. But more than half of the 5,100 species of coral on the planet exist in cold, deep and dark parts of the world's oceans. These cold-water corals can grow and form structures called mounds. Some of the largest cold-water coral mounds on the planet are over 100m in height and several kilometres in length. In fact, many of these world class examples can be found just offshore Ireland in water depths of down to 1000m.

Although originally discovered by fishermen, early scientific records of cold-water corals, dating back to 1755 in a book named The Natural History of Norway, describe them as "white" and "like a flower in full bloom". Since then, many early deep sea expeditions have been conducted where cold-water coral samples were collected by dredge. Dredging involves a ship towing a large metal frame so it is dragged over the seabed and any broken off debris (or coral) could be collected in a chain mail bag.

Scientific methods have evolved significantly since then. Over the past 20 years, using a variety of cutting edge methods and ever-developing technologies, Irish scientists have been studying world-class examples of cold-water corals habitats offshore Ireland. One such method, known as multibeam sonar, sends pulses of acoustic energy to the seabed which are reflected to the surface and these reflections can be converted into maps of the seabed.

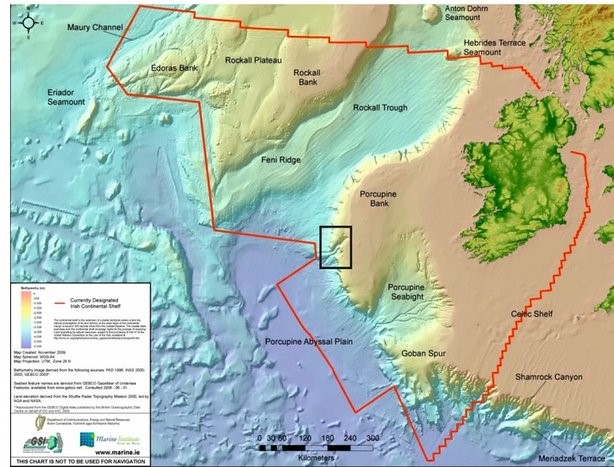

The real map of Ireland showing the location of the Porcupine Bank Canyon (black box). Map courtesy of the INFOMAR program (Marine Institute and Geological Survey, Ireland).

Ireland is a world leader in seabed mapping, being one of the very few countries in the world to have its entire seabed mapped at such a high standard, thanks to the INFOMAR programme. These maps have been used to identify some of the ‘giant’ cold-water coral mounds offshore Ireland.

In 2019, a team of researchers from UCC completed two offshore research expeditions onboard the Marine Institute's RV Celtic Explorer to the Porcupine Bank Canyon, some 300km due west of Dingle, Co. Kerry. The Porcupine Bank Canyon is a 70km long, 800m high submarine canyon in the North East Atlantic Ocean which is home is a strikingly diverse range of cold-water coral habitats.

Here, cold water coral mounds grow along the edge of an 800m high canyon wall. Moreover, corals grow along this vertical wall, feeding on organic material funnelled into the canyon. Interestingly, at 3500m water depth along the base of the canyon wall, is a large build-up of coral rubble, where any broken pieces of coral from above end up, a process which appears to have been ongoing for thousands of years.

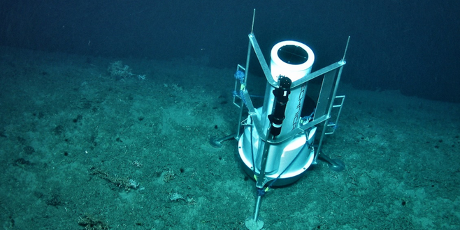

The research expeditions were specifically to understand why such a diversity of coral mounds existed within the canyon. To do this, the team carefully deployed a number of monitoring systems around these coral mounds for three months. The monitoring systems, called "landers", were specifically developed to measure currents, temperatures and trap particles of food, sediment and microplastics.

The Holland 1 ROV deploying one of the landers from the RV Celtic Explorer at the Porcupine Bank Canyon. Photo: Zoe O'Hanlon/Simply Blue Energy

Given the complexity of the seabed, the team used the Holland 1 Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) to navigate the canyon and deploy the landers. To map these areas in extreme detail, the team used ROV Photogrammetry, where the lush coral habitats are imaged using the ROV HD cameras and then digitally reconstructed in 3D using a digital mapping software.

Initially. the most shocking finding was plastic which was found at a depth of 2,125m, but early results also show that the canyon is an extraordinary place. Each of the individually mapped coral mounds were strikingly different, some with over 75% live coral while others are composed almost entirely of coral rubble. Equally, current speeds varied from just 2cm per second to over 100cm per second at 700m water depth. Globally, our oceans are showing signs of acceleration and results like this are vital to understand how our cold water corals will respond so we can effectively manage Irelands marine resource in the face of climate change.

Research continues and work is now underway to determine if microplastics are impacting these coral mounds. Recent work carried out by the author shows that Irish coral habitats are showing signs of change. The team are just weeks away from their next expedition to determine what may be driving this. Although difficult to determine, repeat research expeditions over the past ten years are helping to shine a light on Irelands cold-water corals. Marine science has come a long way since the days of dredging, and Irish Science is right at the forefront.

The research expeditions are funded by the Marine Institute’s National Marine Research & Innovation Strategy 2017-2021. Scientific research is funded through a number of programs including the Science Foundation Ireland, Marine Institute, H2020, Aerial Sparks program, Irish Centre for Research in Applied Geosciences and Geological Survey, Ireland. Dr Aaron Lim will be taking part in the Aerial/Sparks online conversation series for the Ars Electronica Festival as part of Galway 2020