|

Chronology of Gerald Griffin

|

| |

See also his Bibliography. |

| |

|

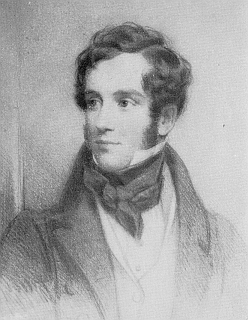

| 12 December 1803 |

Gerald Griffin was born in Limerick into a kind of middle class

that he has often portrayed in his fiction: the substantial Catholic

farmer. He was the twelfth of the fifteen surviving children in his

family. His father, Patrick Griffin, was a brewery farmer, and his

mother, Ellen Griffin, of the ancient Gaelic family of the O'Briens,

was very cultivated and much interested in literature. |

| |

|

| Around 1810 |

When he was seven or eight years old, the family moved some

twenty-eight miles westward from Limerick into a house named Fairy

Lawn, where he had an idyllic childhood with a close-knit family. He

received a good classical education which was often of a scrappy and

haphazard nature, reflecting both his father's declining fortunes

and the whole character of Catholic education at this time. He was

also deeply influenced by the beautiful surroundings of the house,

situated on a hill above the Shannon estuary, with a beautiful

contryside through which Ireland's biggest river reaches the sea. It

was probably there where his poetic imagination had its first

impressions of natural beauty which he conveyed so often in his

fiction. |

| |

|

| 1820 |

Patrick Griffin, having failed in various business enterprises,

decided to emigrate with most of his family to Pennsylvania. Gerald

Griffin remained in Ireland, as well as his older brother, Dr

William Griffin (1794–1848), with whom he went to live in Adare, co.

Limerick. He never saw his parents again and this sundering of the

family circle clearly had a devastating effect on his sensitive and

vulnerable nature. |

| |

|

| 1823 |

He had already thought in the past in following his brother's

footsteps in medicine, but had finally abandoned the idea, and a

meeting with John Banim influenced his choice of a literary career.

Banim's play Damon and Pythias had been successfully

produced at Covent Garden in May that year, with William Charles

Macready and Charles Kemble in the title roles. |

| |

|

| 1823 |

Gerald Griffin completed a full-length tragedy, Aguire

(now lost). Reluctantly, William let him try his luck for making a

literary career in London, after being extremely impressed by the

quality of the piece, and Gerald left Adare. Unfortunatey, his

ambitions received an early set-back when he submitted his tragedy

to the judgement of a London actor, probably Macready, and was

rejected. |

| |

|

| January–May 1824 |

A letter of February indicates that Gerald had already completed

his play Gisippus, with four acts of which he gave to Banim

for suggestions. In the mean time, Gerald was also associated with a

Spanish Friend, Valentine Llanos, in a project for translating

Spanish works into English, hoping to make some money from this. The

bleakest time of his London experience occured for the first six

months of this very year, when he was impoverished and in poor

health, depressed by bad news of his brother's illness and by the

death of various relatives and desperate by the fact that he was

constantly running backward and forward in his career with doubts

that he would ever make any mark in the literary world. His

relationship with his well-wishing friend Banim had gradually

deteriorated, even if he tried to help him offering suggestions for

his novels, meetings with influential people, or financial aid.

Gerald declined all his invitations and finally neglected his

friend entirely and disappeared from everyone's view for a

while. |

| |

|

| June 1824 |

He came back and started to make a living by writing under a

wide variety of pseudonyms for various London journals, including

the Literary Gazette and the News of Literature and

Fashion. On the 5th, the first of nine other pieces, Irish

Satire, indexed in the Literary Gazette under the

general title Horae Monomienses came out. His work is based

on his knowledge of Irish customs and consists mainly of pieces in

which the Irish and their practices are explained and interpreted to

an English audience. He had a 'feeling that he must offer himself as

interpreter of a Gaelic-speaking people and of an emergent

Anglo–Irish, [and this] is to be characteristic of all of Griffin's

prose output and is to affect his writing to the very end.'[1] |

| |

|

| 1825 |

Griffin started to write regularly for the periodical The

News of Literature and Fashion some sketches of London life and

sent them anonymously, refusing for a long time to reveal his

identity to the editor, who seemed to have tried hard to discover

his contributor's name. They finally met, and Griffin got the

reviewing department of Walker's paper, and became a critic

and regular theatrical reviewer. John Cronin has remarked that

there was a huge difference between his works for both

newspapers. Here Griffin was playing the role of the

fashionable London journalist, and all traces of his Irish

nationality were erased. He despised much of what he did for The

News of Literature and Fashion, but his ceaseless activity

inside the newspaper shows how large had been the range of his

interests: comic verse, reviews of books and plays, articles on

opera etc. However, he soon concluded that the London theatre,

controlled by a handful of powerful actor-managers, was interested

only in grand spectacle, and that his serious drama would not

prosper in such a climate. |

| |

|

| 1826 |

Gerald started to take an interest himself in writing a

collection of Irish stories, which was rather tough for him to focus

on because of constant pressure at work. The News of Literature

and Fashion ceased publication that very year. Griffin finally

completed his work and Holland–Tide came out. |

| |

|

| 1827 |

Feeling that this success had given him a foothold in the

library world, and at the insistence of his brother William, Gerald

left London and so the most painful and critical part of his early

experience, and returned home with his brother to Ireland. His

second volume of stories, Tales of the Munster Festivals

came out. It seems that his London experiences which had so

embittered him in some respects also had more positive and

beneficial effects of providing him with a measure of detachment on

Irish issues as we can see from the introduction. Critics would

reproach him later to have lost this mature and fruitful attitude to

his work as an Irish expatriate novelist, when he took refuge in an

'ideal Ireland' in The Invasion (1832). |

| |

|

| 1829 |

That year saw Griffin's best and most celebrated novel, The

Collegians, which combines a hero whose psychology paralleled

the author's own with a vivid depiction of a society in decay. This

same year, he attended lectures in Law at the newly opened

London University. Later, he published another three volumes of

diction containing two long stories, The Rivals and Tracy's

Ambition, which appeared under that joint title. Shortly after

this attempt to acquire a formal education, Griffin got into the

lengthy preparation of his historical novel, The Invasion.

This task took him to libraries in Dublin and elsewhere in search of

material. |

| |

|

| 1830 |

For several months he had a close-knit friendship with the

Fishers who deeply admired his work (at this time, he was writing

The Christian Physiologist) and probably felt in love with

Lydia Fisher, daughter of the well–known Irish Quaker writer Mary

Leadbeater and wife of Jack Fisher, a properous Quaker merchant of

Limerick. This ambiguous relationship with the charming and literary

woman saw a correspondence and verses exchanged between the two of

them, but the different religious persuasions brought Gerald's

friendship with the family to an end. However, both Gerald and Lydia

continued to write to each other. |

| |

|

| 1832 |

Thomas Moore had been offered by the electors of Limerick to

stand for the representation of the city. So, Gerald Griffin with

his brother William were asked to be the bearers of the letter and

bring it to Moore. Thomas Moore declined the offer but gave them an

opportunity to enjoy his society, about which they were extremely

delighted, and Gerald would describe it in great detail later, in a

letter addressed to Lydia Fisher. |

| |

|

| 1835 |

Tales of My Neighbourhood was eventually published that

year. This was the last collection of his tales published before his

death. He also paid his last visit to London this very year to see

his editors. |

| |

|

| 1836 |

He surprised his family by making a visit to France. The purpose

and precise destination of this visit still remain a secret. On his

return, he resumed his life of regular study and devotion. |

| |

|

| 1837 |

He appears to have spent the year quietly at home. It seems that

he had once discussed with Daniel, his brother, the possibility of

having a vocation for the priesthood. Griffin's thoughts were

turning more and more to the religious life. His sisters, Lucy and

Anna, had already entered convents and he was deeply saddened by the

recent death of his beloved cousin, Matt, in India. |

| |

|

| April 1838 |

Daniel convinced him to go on a three-week trip to Scotland

which they both enjoyed as well as the sightseeing. Daniel had

included in his Life diverse extracts of Gerald's notebook

about the trip. |

| |

|

| September 1838 |

Gerald informed his family of his intention of joining the

Christian Brothers' Teaching Order. He entered the novitiate at

North Richmond Street, Dublin on September 8. He seems to have

embarked on his new career with intense dedication, abandoning his

literary work entirely. He was then admitted to the religious habit

on the feast of St Theresa and embarked on a two-year novitiate. It

seems that his distaste for his earlier vocation had been allayed to

the extent that he was willing to undertake the composition of a few

tales of a pious nature, but it also appears that he has been

desperately determined to avoid as much as possible the renewal of

old contacts and the reopening of painful associations with Lydia

Fisher or his sister Lucy. Most of his papers were destroyed by

Gerald himself, preserving only a few poems and the tragedy,

Gisippus. |

| |

|

| 1839 |

In June Gerald was transferred to the Cork house of his Order,

at the North Monastery, where he continued to teach and to practise

his chosen spiritual life. The Christian Brothers were at this time

engaged in the production of their first set of school books and it

appears that Gerald helped with the editing of these

and contributed some of his own works to the new volumes. His

literary enthusiasm was far from completely dead, despite his

previous wish to stop writing. He was at this time, in fact, engaged

on the unfinished story The Holy Island. |

| |

|

| 1840 |

He contracted

typhus fever and died a few days later, on 12 June 1840. He was

buried in the community's graveyard on 15 June. In the same year,

Gisippus had a successful production at Drury Lane, with

Macready in the title role. |

| |

|

| 1842 |

A final set of stories, Talis qualis, or, Tales of the Jury

Room was published posthumously. |

Footnotes

1. Gerald Griffin 1803–1840: A critical

biography, John Cronin.

Sources:

John Cronin, Gerald Griffin (1803–1840): A Critical

Biography, Cambridge University Press 1978.

Daniel Griffin,

The Life of Gerald Griffin, by his brother. London, Dublin

& Edinburgh: Simpkin and Marshall, 1843.

See also John Cronin, 'Griffin, Gerald (1803–1840)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (online at http://www.oxforddnb.com).

Compiled by Juliette Maffet (Université Blaise Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand), February 2012, with

assistance from Beatrix Färber.

|